![]() November-December 1999

November-December 1999

By Robert Peterson

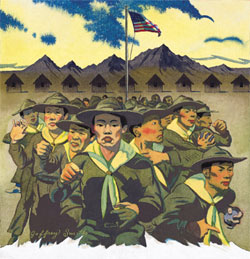

Illustration by Jeffrey Smith

During the Second World War, hundreds of Boy Scouts from the West Coast set a camp attendance record that will never be challenged. They were Japanese-American Scouts who were sent with their families to detention camps well inland from the coast soon after the Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. Some Scouts spent three years in camp.

More than 110,000 people—two-thirds of them American citizens—were herded into 10 detention camps in seven states: two in California, Arizona, and Arkansas, and one each in Colorado, Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming. They lived in hastily constructed barracks surrounded by barbed wire fences and guard towers.

Scouting flourished at all 10 detention camps. The most flourishing program was at the Heart Mountain camp near Cody, Wyo. Its seven troops and four Cub Scout packs made up a separate district in the Central Wyoming Council.

William Shishima was a member of three of the troops in his three years at Heart Mountain with his family. At 12 he joined Troop 145, chartered to the Maryknoll School in his native Los Angeles. Later he joined Troop 333 of St. Mary's Episcopal Church in Los Angeles. Still later, he became a Life Scout in Troop 379 of the Koyasan Buddhist Temple in Los Angeles. (After the war, back home in Los Angeles, he reached Eagle rank.)

"We had very active troops [in the detention camps]," Bill Shishima said. "We played baseball and basketball games, and we went camping along the Shoshone River" just outside the camp. Before the war ended and the camp closed in 1945, he went to summer camp with Troop 379 at Yellowstone National Park.

Advancement was a problem. Cooking equipment and supplies were hard to get. The required 14-mile hike for First Class rank was difficult unless the Scout wanted to get shot for leaving the detention camp.

Swimming tests were hard to pass until the Heart Mountain Scouts made their own pool. In two and a half months, with only shovels and other hand tools, the Scouts dug out a pool 150 by 300 feet and 15-feet deep at its deepest. During the cold Wyoming winters, the pool doubled as a skating rink.

Junichi Asakura, who was an 18-year-old assistant Scoutmaster of Troop 379 when his family was interned, recalled that the troop sometimes camped inside the fence at Heart Mountain, although never out of sight of the barracks. "Every day we raised and lowered the American flag at the camp headquarters," he said. "We were very loyal to the United States."

Like nearly all the Japanese-American Scouts in the camps, Asakura was a Nisei (American-born sons of Japanese parents, who were called Issei. By law, Issei could not become naturalized citizens).

Weren't the boys and parents resentful of being relocated without cause? "Actually, our leaders seemed to handle us well to the point that we never thought about it," Asakura said. "In fact, our Scoutmaster, who was an American veteran of World War I—we all looked up to him—he didn't seem resentful at all. Somehow he carried us through the crisis."

Another member of Troop 379, Albert Ibaraki, recalled, "My parents were Issei, and they told me to be loyal to the United States because it was my country."

Francis Kikuchi, 74, was 16 when he was interned at the Manzanar Relocation Center in eastern California. "My children say something to the effect that we should have been bitter," he said. "But in those days, my generation was a lot more docile. We followed our parents' advice and we obeyed the law. If the law said you have to move into a camp, we did."

Bruce Kaji agreed. He was also at Manzanar as a 16-year-old former Scout. "We accepted the situation as the government had ordered us," he remembered. "There was no discussion as to choices, why we were there, or when we were going to be released."

At Manzanar, on the eve of the first anniversary of Pearl Harbor, the most noteworthy incident involving Scouts in the detention camps occurred.

The tensions between pro-American and pro-Japanese internees overflowed. A thousand protesters gathered at the administration building; one started for the flagpole, to tear down the U.S. flag.

"The Boy Scouts surrounded the base of the flagpole," the center's director, Ralph P. Merritt, told the Associated Press. "They had armed themselves with stones the size of baseballs [and] defied the agitators or the whole mob to touch the flag. And the flag was not hauled down."

The incident did not, however, end the riot. Military police opened fire when internees began throwing stones. One man was killed, another fatally injured, and seven others wounded.

The official explanation for interning Japanese aliens and American citizens of Japanese ancestry was a fear that they might aid an invading force from Japan. But not a single case of sabotage was ever proven against a person of Japanese ancestry.

In fact, a major cause was racism, buttressed by economic interest. Thousands of interned Japanese, citizens and aliens alike, had to sell their farms and businesses at bargain-basement prices.

And yet the overwhelming majority of Japanese citizens were devoutly loyal to the U.S.A. About 26,000 Nisei served in the American military, some volunteering from the detention camps.

The all-Nisei 442nd Regiment Combat Team, which fought in Italy, became the most decorated unit of its size in the Army.

More than four decades after World War II ended, Ronald Reagan signed into law the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. It acknowledged and apologized for the injustice of the wartime evacuation, relocation, and internment and authorized a redress payment of $20,000 each to an estimated 60,000 persons still living who were affected by the evacuation.

Robert Peterson is the author of The Boy Scouts: An American Adventure.

| The Boy Scouts of America | http://www.scouting.org |