By Layne Cameron

Photographs by Steve Seeger

|

| His vision impaired by a blindfold, this Webelos Scout is able to find his direction by the touch of his fingers on a Braille compass |

A car accident left Terri Cecil-Ramsey paralyzed but could not foil her Olympic dream. A motorcycle accident took Tim Farmer's lower right arm but could not extinguish his passion for hunting and fishing.

Cecil-Ramsey lost a basketball scholarship to Kentucky Wesleyan University. But during rehabilitation she learned she could still play basketball (the wheelchair version) and she harbored a penchant for fencing.

Developing her fencing skills, she made the United States team for the 1996 Paralympic Games in Atlanta. There she reached the quarterfinals, the only U.S. competitor to win any bouts.

Having only one arm couldn't hold Tim Farmer back, either. His work with the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife led to his becoming the host of "Kentucky Afield," a local outdoors TV show. And using special equipment, he hunts and fishes as much as ever.

On an October weekend in western Kentucky, both Tim Farmer and Terri Cecil-Ramsey were guests at the Challenge '97 Disability Awareness Camporee, hosted by the Owensboro-based Shawnee Trails Council.

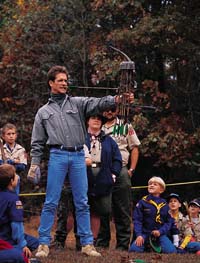

Scouts watch Tim Farmer, who lost his lower right arm in an accident, demonstrate his one-arm (plus strong teeth) archery technique |

Scouts watched in amazement as Farmer held his compound bow with one arm and used a special tab to draw the arrow back with his teeth. They cheered as he nailed the bull's-eye not once, but six straight times.

At first campers were pleased just to be on the basketball court with Cecil-Ramsey, whose recent honors include being named Miss Wheelchair America. The Scouts soon were even more impressed, however, with how well she could thread the needle of a give-and-go pass with pinpoint accuracy.

Scouts saw past the wheelchair. In their minds, they were playing basketball with a world-class athlete. Likewise, on the target range, they didn't see a one-armed archer but a favorite local TV star who could also outshoot anyone in camp.

For Peter Kafer, district executive and camporee adviser, this meant "mission accomplished." A key goal for Challenge '97, he explained, was to show campers how individuals with severe limitations can lead active, wholesome lives.

A second, equally important, camporee goal was to let Scouts and Scouters experience being disabled and showcase devices that aid the disabled.

Not as easy as it looks: Scouts try their best shots bowling from a wheelchair |

Kafer drew inspiration from an article in Scouting magazine ("Handicapping Campers for Fun and Understanding," March-April 1997) and by seeing wheelchair basketball, beep baseball, and one-arm archery at the 1997 National Scout Jamboree. "I realized that this area has more possibilities than I ever dreamed of," he said.

Organizers assembled a variety of household items and donated materials for the camporee. The Internet revealed many sources willing to help. Western Kentucky Easter Seal Center, for example, provided crutches, for use in the obstacle course and tent-building event.

A ball that beeps lets the visually impaired enjoy softball |

The chairs were used in events from the basketball court to a makeshift bowling alley. And on the archery range, they afforded a firsthand perspective into the challenge of one-arm bow shooting.

Scout David Bertschinger didn't have to pretend he had a disability. Three weeks earlier he had broken an arm, and now he rested his cast in his lap as he sat in a wheelchair on the shooting line.

A "blind" runner's main concern is what's ahead |

As David pulled back on the bowstring, his arrow slid off the rest shelf. He put it back, only to see his first shot fall short of the hay bale target.

Elation replaced frustration, however, as David's next four shots thumped into the bale -- one actually striking the target.

His father, Jeff Bertschinger of Pack 76, Owensboro, watched in amazement. "He actually did better with the one-handed bow than he did at summer camp when he was able to use both hands," he said. "I was worried about bringing David to the camporee," the elder Bertschinger admitted. "That was before we knew about the disability awareness theme, though."

Scouts learned about working through their limitations by attempting to tie knots while blindfolded or while wearing gloves.

Other blindfolded Scouts tried to hit a softball that beeped as it was pitched to them. Or gained insights into dyslexia and other learning disabilities as they attempted to decipher jumbled merit badge instructions.

Deciphering jumbled merit badge names gives insights into dyslexia |

Some activities helped develop individual skills. Others were designed to improve teamwork-pooling abilities rather than focusing on weaknesses.

"Left! Left! Faster, faster! Right! Right!" Scouts of Troop 550, Sturgis, Ky., attempted to guide a blindfolded Bowen Simpson through a 100-foot dash. "It's one thing to close your eyes and try to walk through a room," Bowen admitted. "It's another thing to do this."

To help guide him through his run, Simpson was attached by rope to an overhead cable. At first he still held a mind's-eye view of the course, and his gait was easy. But as his mental map faded, he began to stumble. Then Simpson put his faith in his other senses and strode across the finish to the cheers of his troop.

Getting one "blind" Scout through a race isn't much of a challenge compared with maneuvering an entire patrol through an obstacle course.

"We have to go over this?" questioned Jonathon Blacklock of Troop 173, as he eyed the steps, ramps, slalom of folding chairs, tires, and a barrel that represented what people with disabilities may encounter during a simple walk around the block.

Some Scouts raced quickly through the course. Others seemed content to exchange top times for a bit of enlightenment.

"My brother broke his foot at our last camp-out," said Adam Hayes, Troop 173. "Now I know how he feels."

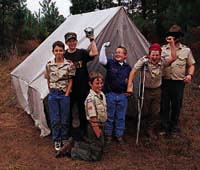

A wall tent challenges a patrol of "disabled" Scouts (one is "blind," one uses only one leg, another only one hand; one can't hear, another can't speak).  The result is an example of teamwork and adaptability. |

That sort of compassion and patience was needed at the "disabled tent pitching" station. Scout teams with different members using one hand, one arm, one leg, or working blindfolded, struggled to set up a tent.

The resulting structures were inside out, cockeyed, or so unstable a light breeze collapsed them. And some teams even left their "blind" partner standing alone or wandering aimlessly.

In the end, however, most teams coordinated their strengths and managed to complete the job.

Among the tent-pitching bedlam, a light of recognition hit Ross Smith of Pack 10. Working with one arm tied to his waist, he experienced exactly what the camp's organizers hoped would happen to everyone at the camporee.

He realized, Smith said, that disabled persons have the ability to work through anything.

Smith imagined himself with a disability in the future. "I want to be a construction manager. If I were paralyzed, and I was working on a roof, I'd just have to have an elevator to get up there," he said. "I could do everything -- except walk -- and that wouldn't be so bad."

Freelance writer Layne Cameron lives in Indianapolis, Ind.

Terri Cecil-Ramsey: 'I Could Do Anything'

"I was great before," says Terri Cecil-Ramsey, remembering her high school basketball career. "But I'm terrible at wheelchair basketball." On the latter assessment, observers at the Challenge '97 Disability Awareness Camporee who watched her wheel up and down the court, whipping passes to her teammates, begged to differ. "Terrible" is definitely not the adjective that describes the hardcourt abilities of Miss Wheelchair America. Cecil-Ramsey's dream of playing basketball in the Olympics was dashed when the car she was riding in struck a telephone pole. She lost the use of her legs, a basketball scholarship to Kentucky Wesleyan, and, for one year, any hope of leading a productive life. "The first year I felt totally devastated," she told camporee participants. "Then I became defiant, believing that I could do anything." Resurrecting her can-do spirit, Cecil-Ramsey graduated from the University of Louisville in 1995. She went on to participate in rock-climbing; fenced at the 1996 Paralympic Games (losing to the gold-medal winner); and, contrary to her own review, can still rule the basketball court. "I still have the same hopes and dreams I had before," she said. "I just sit down a lot more." |

Basic Equipment, Ingenuity Enhance Disability Awareness"Your neckerchief will make an excellent blindfold," announced camporee organizer Peter Kafer at the Challenge '97 opening flag-raising ceremony. With one simple piece of cloth, each Scout could create instant visual impairment needed for many of the day's activities. Other equipment wasn't as simple or as easy to acquire. Nevertheless, camporee organizers assembled a variety of household items and donated materials that helped make Challenge '97 a great success. Wheelchairs, provided by Children of the Americas, were used on the archery range, the basketball court, and on a makeshift bowling alley set up on an abandoned foundation. Crutches, supplied by Western Kentucky Easter Seal Center, were used on the obstacle course and in the disabled tent building station. Other equipment included ropes, to tie Scouts' arms to their sides; duct tape, to seal sleeves over Scouts' hands; and muffler brackets, lead pipes, and pallets to anchor bows on the archery range. Specialty items like a Braille compass, a Braille Cub Scout handbook, and "beep" baseballs also enhanced the event. |

| The Boy Scouts of America | http://www.scouting.org |