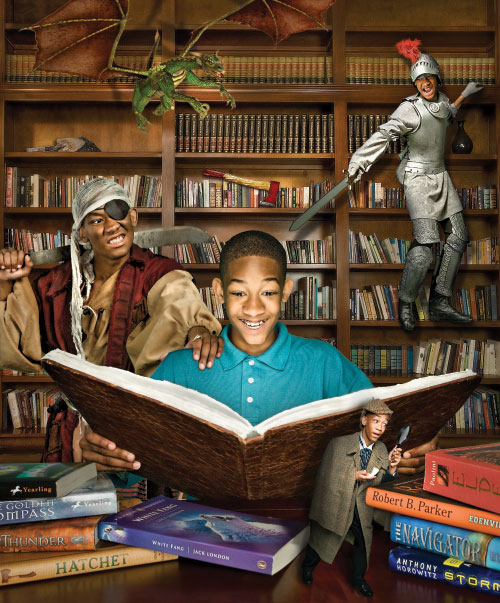

Guys Read Guy Books

By Mary Jacobs

Photographs by Marc and Melanie Chartrand

What's the secret to boys and reading? Give them books about things they like: adventure, biography, science fiction, sports, and yes, even gross humor.

|

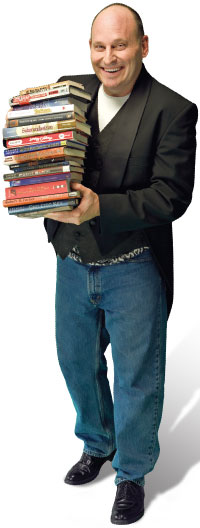

Jon Scieszka, author of The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales, can picture his reading audience quite precisely.

“It’s those knuckleheaded boys who are sitting in the back of the classroom,” he says with a laugh. “I want to engage them and make them sit up.”

Scieszka, recently appointed the National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature by the Library of Congress, isn’t the only one thinking about boy readers. Studies show boys aren’t reading as much as girls, and it’s affecting their success in school.

Scieszka, recently appointed the National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature by the Library of Congress, isn’t the only one thinking about boy readers. Studies show boys aren’t reading as much as girls, and it’s affecting their success in school.

Why?

The short answer, says Scieszka: “Boys often have to read books they don’t really like. They don’t get to choose what they want to read.”

Reluctant readers

In 1955, Time magazine published a groundbreaking article titled “Why Johnny Can’t Read” that argued the reading curricula in American schools wasn’t working.

Now, more than 55 years later, the issue isn’t so much “why Johnny can’t read” as “why Johnny won’t read.”

According to a study published in the book Reading Don’t Fix No Chevys, researchers Michael W. Smith and Jeffrey D. Wilhem reported that boys read less and are less enthusiastic about reading than girls.

Some researchers point to differences in the way boys’ brains are wired, which makes reading a bigger challenge. But a study conducted by the Young Adult Library Services Association highlights another issue—many boys just don’t like to read.

The study polled boys with an average age of 14 about why they don’t read. Their answers included “boring/no fun” (39 percent); “no time/too busy” (30 percent); “like other activities better” (11

percent); “can’t get into the stories” (8 percent); and “I’m not good at it” (4 percent).

The problem seems to begin with a fourth-grade slump. Evidence indicates that’s when boys tend to lose interest in reading, says William Brozo, professor of literacy at George Mason University’s graduate school of education. “Around the middle-school years, motivation to read and learn and actual reading achievement tend to decline among boys.”

Brozo adds that those are the years when masculine identity becomes paramount for boys—and many boys see reading as a “girl thing.”

“They see that mom reads to them most of the time, that mom is the only one at home reading a book, that most all of their teachers in the first several years of school are women, telling them that they should be readers,” he says. “And publishers know that most buyers of books are women.”

“They see that mom reads to them most of the time, that mom is the only one at home reading a book, that most all of their teachers in the first several years of school are women, telling them that they should be readers,” he says. “And publishers know that most buyers of books are women.”

Another factor: Reading assignments often change during the middle-school years, when students begin to tackle thicker books with fewer illustrations.

“Middle school is the point at which students are expected to read ‘more serious’ stuff,’” Scieszka says. “And that turns boys off.”

Fear of failure also may turn off some boys. Boys typically lag behind girls in verbal skills, and their reading performance trails girls’ by about 1.5 years.

“Incompetence is a big fear for boys,” says Paul Mullen, Ph.D., an author and literacy advocate. “If they’re feeling inferior about reading, they’ll downplay it.”

What a boy likes

The bottom line: Boys need more exposure to the kinds of books that excite them. “We know a great deal about the reading interests of teen and preteen boys,” says Brozo.

Surveys and studies show that boys prefer topics and genres such as humor, horror, adventure, informational books, science fiction, crime and detective, ghost stories, sports, war, biography, historical novels, and graphic novels.

Surveys and studies show that boys prefer topics and genres such as humor, horror, adventure, informational books, science fiction, crime and detective, ghost stories, sports, war, biography, historical novels, and graphic novels.

These kinds of books “appeal to boys because the fun overtakes the challenge of reading,” says Brozo. “Boys can overcome the challenges of what might otherwise be a difficult read, if the material appeals to them.”

Boys are more likely to read informational texts and magazine or newspaper articles. They like comic books and graphic novels. Many boys are collectors and will collect series of books.

Boys read less fiction than girls but tend to enjoy escapism and humor. Many boys are passionate about science fiction and fantasy. They like to read stories about their interests such as those related to hobbies or sports. Also, boys tend to resist reading books about female characters, whereas girls aren’t so bothered by books about boys.

Much of that material doesn’t fit under the label of “literature,” but reading experts say that keeping boys engaged is more important than insisting on quality.

Even the literary Brits are starting to expand their definition of what makes good reading to include more boy-friendly topics.

Anthony Horowitz |

Alan Johnson, England’s former education secretary, recently urged every secondary school “to provide a bookshelf packed with spy novels and action stories to help boys catch up with girls.” School libraries need “not just Jane Austen, but a necessary dose of Anthony Horowitz as well.”

Horowitz has written a series of books, starting with Stormbreaker in 2001, that feature a 14-year-old spy named Alex Rider, who’s something of a teenage James Bond. The books have sold four million copies in the United States alone.

Unwillingly recruited to spy for the British secret service, young Alex uses his intelligence and creativity—along with an arsenal of cool gadgets—to fight the enemy.

Unwillingly recruited to spy for the British secret service, young Alex uses his intelligence and creativity—along with an arsenal of cool gadgets—to fight the enemy.

“It’s the world of a boy’s dream,” Horowitz says. “Boys find it very easy to empathize with the character. Boys ‘are’ Alex Rider when they are reading my books.”

Even though he doesn’t aim for a male-only readership, Horowitz says, “I’m the writer for boys who don’t want to read. Over and over again, I meet parents who tell me that, somehow, Alex Rider has got their kids reading.”

The cringe factor

Horowitz says that he relies on the judgment of his 17-year-old son, Cassian, to read drafts of his novels and to catch passages that won’t work with young readers. “If a text is embarrassing, he’ll mark it with the word ‘Cringe.’”

But many teachers and librarians aren’t attuned to what makes boys “cringe”or to asking about what turns them on to reading. Often, teachers or librarians are more likely to dismiss, or even forbid, books that interest boys.

“I liked to read funny stuff when I was

a kid,” Scieszka recalls. “But I had to read

that stuff on the sly.

“If you really like sharks or World War II bombers, and you want to read about them, teachers tend to say, ‘You can’t just read those. It’s not a book,’” Scieszka says.

Brozo cites Katherine Paterson’s Bridge to Terabithia as a good book that’s popular but doesn’t appeal to most boys.

“It’s not simply because the main character is a girl who is more athletic and more clever than the main character in the story, but because the psychological and emotional context of the story makes it less accessible to most preteen boys.

“Is it a flawed novel? Not by any means. Is it a novel chosen by teachers with boys in mind? I doubt it.”

“Is it a flawed novel? Not by any means. Is it a novel chosen by teachers with boys in mind? I doubt it.”

To engage reluctant-reader boys, experts urge educators to expand their definition of reading. Graphic novels, comics, and manga (a Japanese comic-book style) appeal to boys—and though they rely heavily on pictures, they still boost reading skills. In fact, Kaplan Test Prep publishes manga novels featuring SAT vocabulary words as a way of helping high school-age readers, especially boys, absorb the words more quickly than conventional methods like flash cards.

These books may make parents cringe, but if they’re getting boys to read, they’re keeping them in the game and making them likely to tackle more serious material later.

Boy vs. girl themes

Scieszka recalled an instance when he met an 8-year-old boy who was reading Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie with his class and thought the book was “just awful.”

Scieszka says he understood the boy’s attitude. “Little House on the Prairie might be a wonderful book,” he says. “But if you’re an 8-year-old boy, it’s not the book that’s going to light your fire and get you reading.”

Scieszka says he knows what most boys don’t like: “dreary problem novels, where everyone dies and the men are complete snakes.”

Girls tend to veer more toward novels that highlight relationships, and teachers—most of whom are female and many of them English majors—tend to assign those books.

“Boys typically don’t like books about relationships, unless they’re hero-based,” explains Paul Mullen, an author and literacy advocate. “If a book’s central theme is based on relationships, boys will easily become disenchanted.”

“Boys typically don’t like books about relationships, unless they’re hero-based,” explains Paul Mullen, an author and literacy advocate. “If a book’s central theme is based on relationships, boys will easily become disenchanted.”

Horowitz also notes that male readers are sensitive about the age of the characters in books. “My hero is 14, and the age of my readership goes up to age 15. Older boys don’t want to read about younger boys,” he says.

Scieszka cites Gary Paulsen, the author of Hatchet and other boy-friendly books and a frequent contributor of short fiction to Boys’ Life magazine, as the epitome of “testosterone-soaked literature.”

“He gets that guy mentality,” says Scieszka. “He understands that, for a good book, you need weaponry and vehicles. Or you need to be out in the middle of nowhere and just have your hatchet to survive.”

Reading starts at home

Helmer Duverge, a family literacy trainer and an assistant Scoutmaster in Louisville, Ky., says encouraging boys to read should start at home. Parents can model reading by incorporating it into daily activities such as making a shopping list or discussing newspaper articles at the dinner table.

And don’t limit your definition of “reading” to books, Duverge adds. Kids are reading on the Internet, and “as long as they’re reading, as long as you’re talking about it and having a dialogue, it’s all good,” he says.

And don’t limit your definition of “reading” to books, Duverge adds. Kids are reading on the Internet, and “as long as they’re reading, as long as you’re talking about it and having a dialogue, it’s all good,” he says.

“It doesn’t help to force books down boys’ throats or to say that a book is ‘good for them,’” Horowitz says. “It’s got to be a shared enthusiasm.”

Scieszka targets the “boy gap” in reading as he speaks to educators across the country. “The first thing I recommend to teachers and librarians is to expand their definition of what reading is. Any reading is good reading. Let your boys choose stuff.” Scieszka has created a Web site, www.guysread.com, to encourage families and schools to build their own “Guys Read” collections.

Reading opportunities in Scouting

Scieszka, who attended the 1969 jamboree as a Scout, says the BSA can provide a jumping-off point to engage boys. Scouting offers “all that great boy stuff” in ways that are often not encouraged in other school or extracurricular activities.

“You get to learn how to do things like sharpen a knife.” But elsewhere, he says, “you can’t even say the word knife anymore.”

“You get to learn how to do things like sharpen a knife.” But elsewhere, he says, “you can’t even say the word knife anymore.”

“Scout leaders are in an ideal position to influence boys’ reading habits,” says Brozo.

And they don’t need highbrow taste to do so, Scieszka says. “If you’re reading an autobiography of Dale Earnhardt or a tractor manual, that’s great. Talk about it with your Scouts.”

Duverge also touts Boys’ Life as a useful tool for getting boys to read. “It’s an incredible magazine,” he says. “What I enjoy are the real stories of heroic acts. I read those and talk about them with my sons. I ask questions like, ‘What would you do?’ ‘Would you risk your life like that?’ It shows the way Scouting can influence and affect others in a vital, nonfiction way.”

It’s little surprise that reader surveys reveal the comic-style of “A True Story of Scouts in Action” is one of Boys’ Life’s most popular features.

It’s little surprise that reader surveys reveal the comic-style of “A True Story of Scouts in Action” is one of Boys’ Life’s most popular features.

“What we try to do is to engage our readers,” says J.D. Owen, editor-in-chief of Boys’ Life. “We try to make the material entertaining enough that they won’t know it’s educational.”

The aim: Don’t confine reading to schoolwork; instead, make it a lifelong habit. “Remove the stress of reading as an academic pursuit. Make it enjoyable first,” says Duverge.

Writer Mary Jacobs lives in Dallas, Tex.

Recommended ‘Guys Read’ BooksHere are some recommended titles for boys of different ages from Jon Scieszka’s GuysRead.com Web site. YOUNG GUYS Cars and Trucks and Things That Go, Richard Scarry Go, Dog. Go!, P.D. Eastman The Stupids, Harry Allard; illustrated by James Marshall The True Story of the 3 Little Pigs!, Jon Scieszka The Maestro Plays, Bill Martin and Vladimir Radunsky MIDDLE GUYS A Series of Unfortunate Events, Lemony Snicket The Baseball Card Adventure Series, Dan Gutman Bud, Not Buddy, Christopher Paul Curtis The Giver, Lois Lowry Sideways Stories from Wayside School, Louis Sachar The Day My Butt Went Psycho, Andy Griffiths October Sky, Homer Hickam Brian’s Hunt; The River; Hatchet, Gary Paulsen Artemis Fowl books, Eoin Colfer Alex Rider books, Anthony Horowitz The Phantom Tollbooth, Norton Juster OLDER GUYS The Golden Compass, Philip Pullman Ender’s Game, Orson Scott Card The Illustrated Man, Ray Bradbury Oddballs, William Sleator Redwall books, Brian Jacques Eragon, Christopher Paolini Tomorrow, When the War Began, John Marsden The Outsiders, S.E. Hinton White Fang; Sea Wolf, Jack London |