![]() January-February 2001

January-February 2001

By Robert Peterson

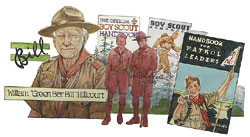

Illustration by Joel Snyder

If you were a Boy Scout 30-odd years ago, William Hillcourt needs no introduction. He was "Mr. Boy Scout," far better known to Scouts than the Chief Scout Executive or any other official.

Hillcourt was a fixture in Boys' Life magazine. Writing as "Green Bar Bill," he dispensed woods wisdom and Scoutcraft tips in every issue. He also authored several BSA manuals, including three editions of The Boy Scout Handbook. His formidable enthusiasm for the outdoor life and for Scouting's ideals shone through every piece he wrote.

Given Hillcourt's beginnings, he seemed an unlikely candidate to become an American Scouting icon. He was born in Denmark on Aug. 6, 1900, the third son of a prosperous building contractor, and was christened Vilhelm Hans Bjerregaard Jensen—a mouthful in Danish or any other language.

For Christmas 1910, Vilhelm received a copy of the Danish translation of Scouting for Boys, the book by Robert S. S. Baden-Powell that had helped launch the Scouting movement in 1908. Within weeks, young Wilhelm had formed a patrol and was camping regularly in a clearing in a beech forest, and, not incidentally, picking up the Scoutcraft tips that he would pass along to American Scouts for more than five decades.

Vilhelm progressed through the ranks of Danish Scouting, earning the Knight-Scout badge—the equivalent of our Eagle Scout Award—and by 25, he was a Scoutmaster.

He earned a diploma in pharmacy, although he never practiced the profession. Instead, he made a haphazard living by writing and editing newspapers in Copenhagen and publishing three books for young readers.

Vilhelm was restless and decided to tour the world. He began traveling in Europe and wound up in the United States in 1926. He was just "passing through," he said later, but he went to work at a Scout camp at Bear Mountain, N.Y., and then at the Supply Service of the Boy Scouts of America in New York City. The experience changed his name and his life.

At the time, he was known as Vilhelm Bjerregaard, having dropped the last name Jensen. "The girls in the national office of the BSA had trouble with Bjerregaard," he said years later. "It came out like 'beer garden,' and I thought that was a little bit too much for the Boy Scouts."

Freely translated, "bjerre" means "hill" and "gaard" means "court," so William Hillcourt he became. (Although he wrote clear and idiomatic English, Bill Hillcourt retained a hint of a Danish accent all his life.)

His other life-changing incident was a chance encounter with James E. West, the first Chief Scout Executive. Making small talk, West asked, "What do you think about the Boy Scouts of America?"

Bill Hillcourt's answer was an 18-page, single-spaced memo in which he dissected the BSA's strengths and weaknesses. He had some good things to say about American Scouting, but he criticized the mania for collecting large numbers of merit badges, the penchant for giving medals for inconsequential achievements, and the relative luxury of its camps.

Most important, he said, troops were not using the patrol method espoused by Baden-Powell and fervently promoted by Hillcourt.

James E. West knew a valuable contributor when he saw one, and shortly thereafter Bill Hillcourt joined the BSA's Editorial Service. Following through on his lengthy memo to James E. West, he was assigned to write the first Handbook for Patrol Leaders. It was published in 1929 and translated into five other languages for use around the world.

From 1932 to his retirement in 1965, Hillcourt wrote Boys' Life's "Green Bar Bill" column, always extolling the patrol method and telling Scouts how to become better hikers, campers, and all-around Scouts. (His signature nickname came from the two green bars that were the emblem of a patrol leader.)

He was also the author of the first Scout Fieldbook; the sixth, seventh, and ninth editions of The Boy Scout Handbook; and numerous other Scouting manuals.

Hillcourt wrote the ninth edition of the Handbook as a labor of love. He was several years into retirement when the Boy Scout program was revamped drastically. Many of the traditional Scouting skills were eliminated. In their place, Boy Scouts were given advice on drug abuse, how to treat rat bites, how to hike in the city, and how to introduce a guest speaker. The revisions, introduced in 1972, were the result of a study titled "Is Scouting in Tune With the Times?"

"Scouting had never been in tune with the times!" Hillcourt protested. "Even in 1908, it was idiotic to suggest that you should go out and do camping because everybody knew that the night air was bad for you—you might get malaria, for heaven's sake. ... It was exactly because [of the facts that] it was idiotic and out of tune with the times that made Scouting appealing. It goes back to the atavistic thing that is supposed to be in every human being to play Tarzan and Robinson Crusoe and so on."

Many Scout leaders agreed with Hillcourt's criticism of the new program changes. By the mid-1970s, the BSA's leaders had decided to take Hillcourt up on his offer to write a new Boy Scout Handbook to replace the eighth edition that had introduced the revised program.

Working for a year without compensation, Bill Hillcourt, with advice from a task force of volunteers and professionals, produced a manual that was redolent of Boy Scouting's old emphasis on camping and life in woods and fields. It was acclaimed as a fitting capstone to his years as "Mr. Boy Scout."

In addition to the books he wrote for the BSA, Bill Hillcourt authored the first definitive biography of Scouting's founder, titled Baden-Powell: Two Lives of a Hero, as well as several books for the general trade on nature and outdoor life.

At the time of his death, on Nov. 9, 1992, in Stockholm, Sweden, during a trip around the world, he had received virtually all national and international honors available to an American Scouter.

Copyright © 2001 by the Boy Scouts of America. All rights thereunder reserved; anything appearing in Scouting magazine or on its Web site may not be reprinted either wholly or in part without written permission. Because of freedom given authors, opinions may not reflect official concurrence.

| The Boy Scouts of America | http://www.scouting.org |